By the end of the 1990s, cinema was a century old; the art of making movies still evolved in unique ways. Animation just had an overhaul thanks to computers and the popularity of Toy Story. Green screen immersion was getting good enough to transport us into unimaginable places like The Matrix. More than anything, filmmaking was embracing technology in ways that made movies more expensive to make. However, the box office returns for these movies were worth the risk for studios. So it’s surprising that a film made with an extremely low budget, a camcorder, and some creativity burst out and became one of the top films of 1999. The Blair Witch Project took people by storm.

If it were released today, it wouldn’t be all that special; but that’s because it paved serious paths for the future of cinema. It’s a movie worth examining because of how it was made, how it was marketed, and why its story feels iconic now, 25 years later.

Taking Found Footage Mainstream

I’m not here to argue that The Blair Witch Project was the first film to create the “found footage” style. There are definitely arguments to be made that Orson Welles did it in the 1970s. Or that a movie like 1991’s America’s Deadliest Home Video used a camcorder as its main way of capturing footage; but I do think that The Blair Witch Project popularized the style. It went from being a gimmick to being a respected way to make a movie. Horror filmmakers have used it to mixed results, but you can’t deny the success of the Paranormal Activity franchise or Cloverfield. I’d argue that those films never get made without The Blair Witch Project.

This style of film also derives from what happened in the 90s when it came to documentary television. This was a time period when cable TV channels like TLC, Discovery, and The History Channel featured camcorder footage in shows about ghost hunting, cryptozoology, and alien phenomena. Thanks to the average person owning a video camera by the end of the century, we could use footage shot by anyone and add it to a documentary. These shows, usually shown late at night, became hits with audiences. Before reality shows co-opted educational cable channels, the “horror-esque” documentary shows were the bread and butter of these channels. Whether they knew they were tapping into the cultural phenomenon of these shows or not, young filmmakers Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sanchez, film students at the University of Central Florida, would capitalize on this approach to horror.

Improvising a Movie

Comedy films usually give actors the space to improvise scenes. If not directly built into the script, additional shots are allowed in order to make the best of something. That isn’t the case in many other genres, so it’s unique to know that The Blair Witch Project had a short 35-page script. Most of the film’s dialogue was made up by the actors, as were many of the camera shots since they were the ones holding the camera. In fact, the process of improvisation began with auditions where no script was given. Heather Donahue, Michael Williams, and Joshua Leanard would end up with the main roles in the film, and controversially, they endured much during the filming process.

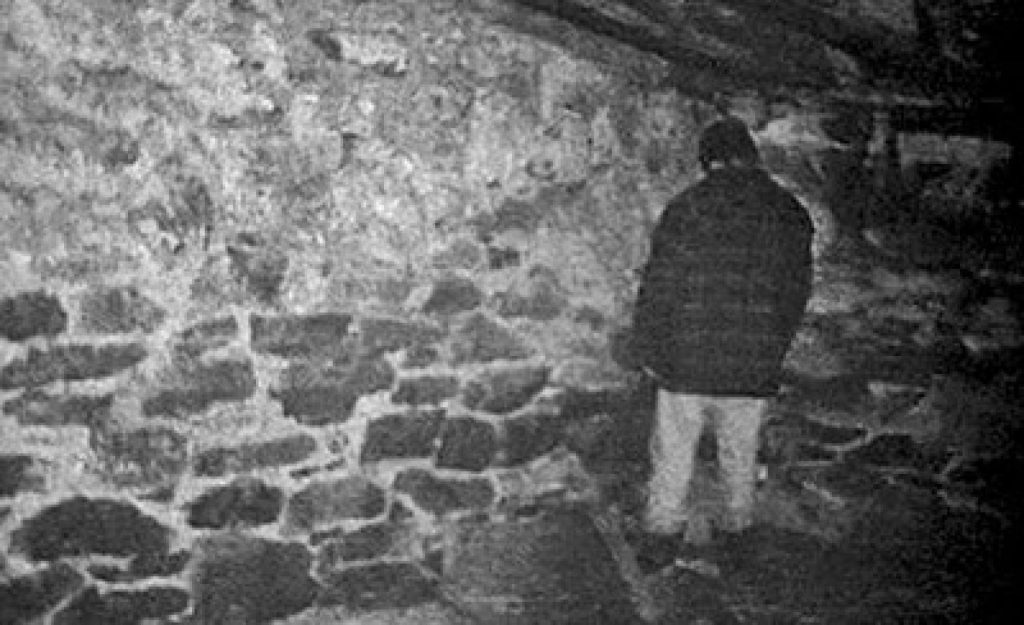

Shooting on location in Maryland, the actors were given clues each day about where to go next and were asked to film and improvise what was happening. During the evenings, the crew would torment the actors, and they would be deprived of meals. Authenticity or not, this kind of practice likely wouldn’t fly in the present day, but it did heighten the improvised scenes. Some scenes were even added to the script late in filming, like the movie’s ending of Mike standing in the corner. To further the authentic nature of what was being filmed, the actor’s real names were used, which helped give the film that ghost-hunting vibe of the late-night Discovery channel shows.

Before the Viral Internet Age

The realism of The Blair Witch Project was part of the selling point when it came to marketing. Although the budget for the film was around $60K, the marketing more than doubled that number. It was worth it. At the time of the film’s release, I was in high school, and horror fans or not, it became a major talking point among my peer group. The genius marketing strategy was to make the film seem like it was real with wanted ads for the actors involved, newsreel clips, and a mockumentary that Myrick and Sanchez made about the Blair Witch legend for the Sci-Fi channel (now SyFy) which leaned back into what was popular on cable at the time.

On the new World Wide Web, the film’s website was set up to make it look like the movie was being released in a search effort, and if you were to visit the IMDB page (yes, it was around in the early internet years) you’d see that the actors were listed as missing and presumed dead. I personally remember seeing trailers for the film where the audience from the theater was shown reacting.

It was the first time I had seen that type of tactic in advertising, and it worked. In retrospect, The Blair Witch Project is obviously a piece of fiction, but at the time of its release, conversations about whether or not it was real were rampant, and there was talk of whether or not releasing a movie was right to do since these people were missing. The buzz worked, and The Blair Witch Project would end up being one of the top 10 highest-grossing films of 1999. A film shot on camcorders competed with Toy Story 2, The Mummy, and Notting Hill. It would make more money than that year’s Best Picture at the Oscars, Shakespeare in Love.

We see buzz-worthy marketing campaigns more often now, which is a credit to The Blair Witch Project. The standard of showing a trailer or two on TV and a movie poster at the local cinema became so much more. The viral marketing campaign became something worthwhile and benefited films greatly. 2022’s Smile became a success, not because of its trailer and poster, but because seats were bought at baseball games for actors to sit in and show an evil smile while cameras were on them.

This continued in a variety of places, which helped that film, regardless of its quality, gain traction at theaters. Barbie’s viral campaign not only saw the stars from the film show up in various Barbie-inspired clothing on red carpets and award shows but interactive profile photos were spread online so that anyone could place themselves in it to be their own Barbie or Ken. It would end up being the highest-grossing film of 2023 and a film that would feel more like an event rather than another movie release, thanks partially to its opposition to Oppenheimer but also because the buzz from viral marketing worked so well.

Inspiring a Generation of Video

By the end of the 2000s, YouTube became one of the top sites of the internet and thanks to the evolution in camera technology, anyone could record and upload their own films or videos. While fairly inexpensive cameras for home use existed dating back to the 1980s, those cameras felt more like what your dad would purchase to record birthday parties and family vacations. They weren’t cool. In fact, the only time anyone really ever saw that footage was on America’s Funniest Home Videos.

An argument can be made that The Blair Witch Project changed the perception of the camcorder and, eventually, the digital camera. People interested in filmmaking or just shooting videos grew and skewed younger. Thanks to YouTube, beginning in 2006, there was a place to publicly upload that footage. With thousands of hours of video uploaded every day to the website, it gives people the opportunity to tell their story and reach a large audience.

The fact that The Blair Witch Project was such a low budget film and ended up becoming such a huge success financially and culturally inspired a new crop of filmmakers. The 1990s was a time when new creators began taking over Hollywood from the previous regime. Wes Anderson, Kevin Smith, Sofia Coppola, and John Singleton were filmmakers who established themselves as something different in the 1990s, and while Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sanchez aren’t seen at the same level as those other names, they may have inspired a new wave of creators in the age of the internet, more so than the others.

Their legacy won’t be a catalog of critically acclaimed films; but instead being the godfathers of a new type of movie maker. In horror, 2023’s Talk to Me was a low-budget film by YouTubers Danny and Michael Phillipou that succeeded greatly. Other filmmakers like Casey Neistat or Kogonada have had success both online and off. All of this can be traced back to Myrick, Sanchez, and their improvised film about a witch in the woods.

25 years later, I still think about The Blair Witch Project. While its story is genuinely scary, the film’s legacy is so much more than its plotline. While it adheres to the old idea of “never showing the monster” and does so with great success; I think it’s best known for not relying on the past but instead blazing a new trail for the future. A future that we can understand as an open door for anyone interested in filmmaking to walk through.

For more on Horror, make sure to check back to That Hashtag Show.